Thanks to the Gear Lending Library, I got the chance to try a tilt-shift lens for the first time. Considering myself a wide-angle shooter, I decided to go with the Canon TS-E 17mm F/4 which is the widest tilt-shift lens currently in production. It is also one of the most complex lenses to control since it has 5 inter-related degrees of freedom.

Tilt-Shift Basics

A tilt-shift lens, as obvious as it may seem is a lens which can both tilt and shift. It is possible to have lenses which does one or the other but the major lens makers don’t make such thing. To show what his means, lets start with the shift and my living room.

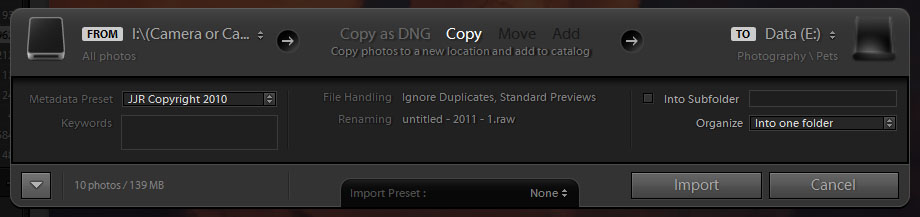

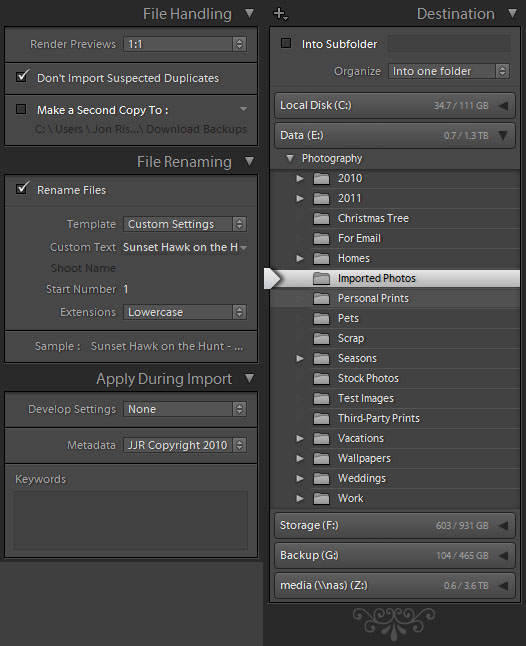

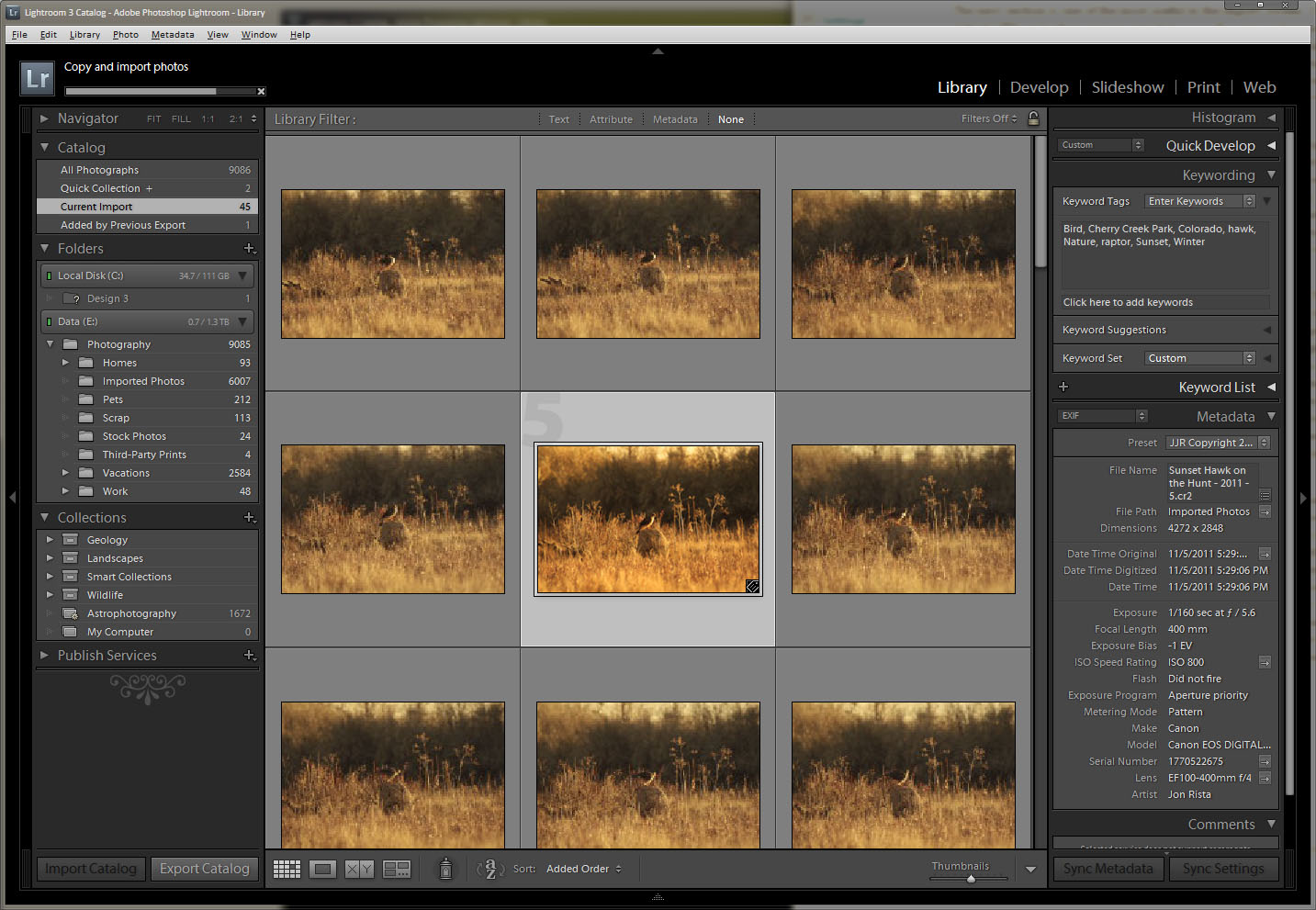

Just below on the left is an image taken with the camera level and the lens in its unshifted position. Now suppose that the couch near the camera was glued to the floor (it feels that way at least) but I wanted an unobstructed view of the window. With a normal lens, all it takes is to tilt the camera up. The result is what you see in the middle. While we no longer see the cough, the room shows some severe perspective distortion, also known as converging verticals. With a tilt-shift lens, there is another possibility meant exactly for this situation: Simply shift the lens upwards. This avoids converging verticals, as seen on the right, because the camera is still level, only the lens has moved up.

The shift feature is extremely useful of architecture photography where it is important to keep the geometry of buildings looking real.

The tilt feature allows to tilt the lens to an angle relative to the camera. What this does it tilt the focus plane. With a normal lens, the focus plane is always parallel to the camera, meaning that everything at a certain distance is in focus. By tilting the focus plane, this no longer holds. Specifically, everything in focus still lies on a plane by that plane is no longer parallel to the camera sensor.

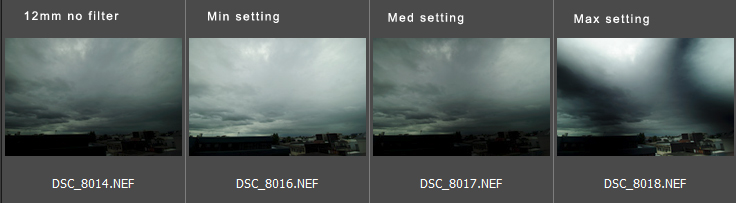

It is hard to conceive and results are sometimes surprising since the plane of focus tilts by an angle which depends on the focal-length, focus-distance and tilt-angle as illustrated in the answer to this question. In the case of the TS-E 17mm F/4, the tilt-angle moves ±6.5°. To illustrate what happens as the lens is shifted, here is a demo of the lens being shifted in 1° intervals.

Note thatf at one point, the plane of focus coincides with the angle of the book faces. At the other extreme, the depth-of-field appears extremely shallow because the focus plane is tilted away from the books.

One artifact which may be limited to some tilt-shift lenses is that changing tilt cause a shift of the angle-of-view. Another member confirmed this is also the case for the Canon TS-E 24mm F/3.5 lens.

Using The Canon TS-E 17mm F/4

Tilt-shift lenses are completely manual except for aperture control which is done by the camera. Tilt and shift have to be controlled manually and so does focus. Now, because the effect of tilt and shift are direction dependent, Canon offers 2 additional controls on their TS-E lenses. One is the lens angle which can be rotated entirely around its optical axis. The second is another rotation between the tilt and shift component. This allows the direction of tilt and shift to be changed relative to each other.

One thing learned early on with the TS-E 17mm is that focus changes with just about any change. Therefore, focus should really be set last among all 5 degrees of freedom. However, before starting to setup the lens, you must meter the scene. To do that, point the camera at the subject with the lens in normal position and take a reading. Adjust to taste and dial those in Manual mode. This is important because once the lens is tilted or shifted, metering no longer works properly and can under-expose by over 3 stops.

The first degree to set should be the rotation of the entire lens. It controls in which direction the shift will occur. A vertical shift is good to avoid converging verticals and a horizontal shift for converging horizontals. Keep the shift plane at an angle is also possible and correct both but since motion is becomes related you have to keep repositioning the camera which gets annoying. Still it eventually works as illustrated in this example which used a 30° angle from horizontal.

The second degree of freedom to set should be the rotation between the shift and tilt. This determines the orientation of the focus plane around the optical axis. A vertical tilt is tilts the focus plane away or towards the camera. A horizontal one tilts it left or right. In the case of the books above, a horizontal tilt is used. For architecture, horizontal can make an entire fence in focus for example.

The third degree to set is the tilt angle. This should be set while observing through the viewfinder since the effect is extremely difficult to predict. Actually, with a camera with Live-View, using that feature helps somewhat. Always set the tilt before the shift because – as mentioned above – tilting causes a shift.

The fourth degree to set is the shift. This is relatively easy to set but with old buildings that are not perfectly straight it is hard to get perfect. Again, Live-View can help here because the image can be seen at a higher magnification. The TS-E 17mm offers a catch here in that you cannot use the full shift and tilt extent together if both axis are aligned with each other. In such cases, Canon recommends that the tilt-angle plus shift-distance never exceed 12. With the axis perpendicular to each other, there is no such limitation.

Finally, the fifth degree of freedom to set is focus. Use DOF-Preview to really see how much the focus plane covers. Before firing the shot though, the TS-E 17mm has knobs to lock the tilt and shift in place. It is recommended to tighten those for the lens not to drift during the shot. Here is an example of a vertical shift and an horizontal tilt to minimize apparent depth of field.

All in all, using a tilt-shift lens opens up a lot of photographic possibilities. It takes a few days to start thinking in terms of shift and tilts but once you get started, the world looks different! Tilt is by far the hardest to predict and align with exactitude but maybe with more time it will be natural.

On a full-frame DSLR the TS-E 17mm F/4 gives a truly wide field-of-view but it also works on a cropped-sensor model as well. I used it with both and was glad to have more than one angle-of-view. Plenty of tilt-shift photos using this lens made it into my Canon EOS 5D Mark III review should you want to see full-resolution samples.

Filed under PhotoSE Gear Grant

Tagged: canon, lenses, tilt-shift

I would tend to say that by definition a professional photographer is a commercial photographers, which means they are trying to make a living with their photography. As such, giving away for free what they are trying to sell to make a living doesn’t really make a lot of sense. To be sure, they could certainly utilize a relatively broad Creative Commons license for certain images that they put out into the world as part of a promotional campaign. But there’s a big concern about giving away images for free, and also about selling images too cheaply. Pricing pressure is immense for professional photographers these days, so they tend to oppose anything that lowers the potential price they can pay (you know, like free images).

I would tend to say that by definition a professional photographer is a commercial photographers, which means they are trying to make a living with their photography. As such, giving away for free what they are trying to sell to make a living doesn’t really make a lot of sense. To be sure, they could certainly utilize a relatively broad Creative Commons license for certain images that they put out into the world as part of a promotional campaign. But there’s a big concern about giving away images for free, and also about selling images too cheaply. Pricing pressure is immense for professional photographers these days, so they tend to oppose anything that lowers the potential price they can pay (you know, like free images).